Image by K. Webster

Image by K. Webster

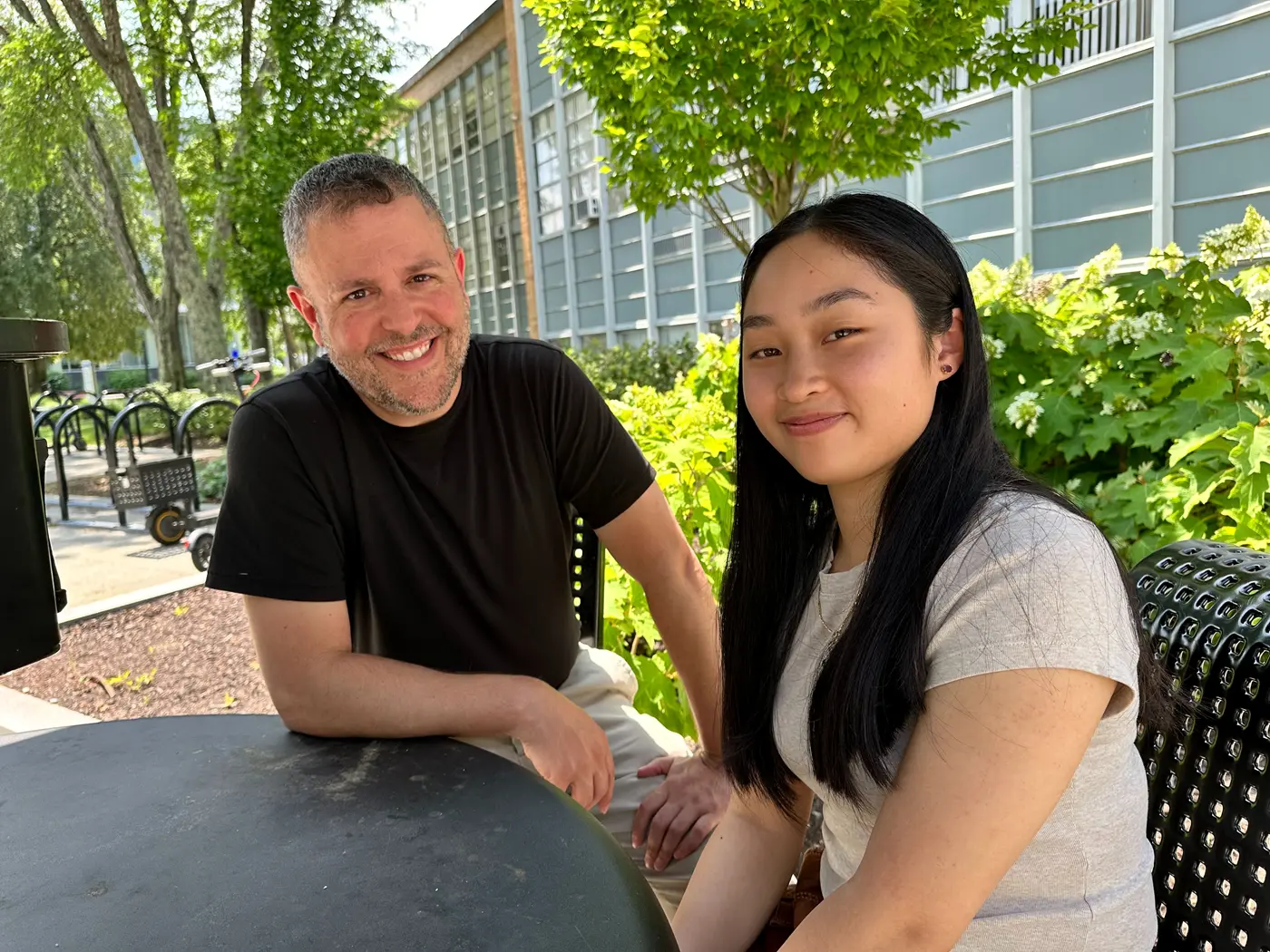

Precalculus Coordinator Matthew Beyranevand, left, and math major Melanie Khiem are researching the K-12 math curriculum and success in college calculus.

Kelly Duong and Melanie Khiem both excelled in their math classes at Lowell High School and UMass Lowell.

But they can’t say the same for many of their friends and classmates, especially after the learning loss that occurred during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Khiem, a math major who works as a tutor and a math class learning assistant, says many of the science and engineering students with whom she works studied calculus in high school, yet had to drop back to precalculus or fundamentals of algebra when they began college because they failed to retain some concepts.

Even Khiem, whose AP scores for Calculus I and II allowed her to place out of those classes at UMass Lowell, realized that she did not know enough precalculus when she began more advanced courses here. She had to play catch-up.

“It hits a little close to home,” she says.

This summer, Khiem and Duong are doing research on two projects to improve mathematics education with Visiting Lecturer Matthew Beyranevand ’03, ’10, the university’s precalculus coordinator.

Each is earning a $2,500 tuition scholarship through Roads to Research, part of the support offered by the River Hawk Scholars Academy, UML’s program for first-generation college students. It’s the first research experience for both of them.

Beyranevand, who earned his master’s and doctorate in math education at UMass Lowell and served as the K-12 mathematics coordinator for the Chelmsford Public Schools for 12 years, says that incoming UML students are often disheartened when they take the university’s math placement test and learn that they must retake precalculus or fundamentals of algebra – courses the university didn’t even offer before the pandemic.

“Students say, ‘Why do I have to do this?’ So one of the things we’re trying to work on this summer is how we can make precalculus more authentically engaging and help students build conceptual understanding at the same time,” he says.

Beyranevand is exploring a nontraditional approach to teaching precalculus: through historical fiction-style stories about real mathematical figures and their discoveries in precalculus.

Duong, a nursing major who recently took a creative writing class in the Honors College, is working on that project. The resulting narratives will be incorporated into the online platform used for all precalculus classes, where they will be available for faculty to use in their teaching, if they wish, and for students to read.

“I selected Kelly because she is such a great writer,” says Beyranevand, who also teaches the history of mathematics. “We’re using real historical figures, but she makes their discoveries into a story, and then I add in the mathematical concepts that I want students to understand.”

The first story Duong is bringing to life is the legend of the fallout between Pythagoras and his star pupil, Hippasus, over the latter’s discovery of irrational numbers.

Image by K. Webster

Image by K. Webster

Beyranevand and nursing major Kelly Duong discuss a story about the discovery of irrational numbers.

Beyranevand, who has published three books about mathematical learning, says that if the stories prove helpful in his and other faculty members’ classes, they could form the core of a new precalculus textbook.

“All textbooks are nearly identical now with their approach,” he says. “But what if there was a textbook written as a collection of short stories that has mathematics built into it, where you explore the math problems as you’re reading it? This is kind of a dipstick to find out if that approach is helpful.”

Beyranevand also hypothesizes that more students are struggling with calculus in college because of a fundamental problem with the K-12 math curriculum: a push over the last two to three decades for the majority of students to study algebra in eighth grade.

Some research suggests that’s fine for students who demonstrate strong math skills, but Beyranevand is skeptical that it helps the typical student.

“What we’re finding is that most students in eighth grade are not ready to think abstractly,” he says. “What I’m exploring is whether it would be better for the majority of students to begin algebra in high school and focus on calculus in college.”

Khiem is reviewing and summarizing existing research on whether students who take algebra in eighth grade, followed by geometry, algebra II, precalculus and calculus in high school, have stronger math skills when they get to college.

From the research she’s done so far, it appears that they don’t.

“There is really no effect from accelerating students’ math courses, which means whether they take algebra in eighth grade or ninth grade, they end up in the same spot,” she says.

Khiem enjoys working with Beyranevand because he values her experience as a tutor and learning assistant.

“It’s really nice to work with him as a partner more than a boss, because I can have some input into whatever we’re doing,” she says. “At the end of this, hopefully we can dig a little bit more and actually create our own research project.”