Image by K. Webster

Image by K. Webster

History major Brandon Bulman, right, and other students examine ancient Roman coins from the Dr. David Menchell Collection.

At the end of a talk for the American Numismatic Society on using coins in the classroom, History Assistant Professor Jane Sancinito made an appeal to collectors who find fakes mixed in with real coins they have bought at auction.

“Please remember your local universities,” Sancinito said. “Many of us would love to have replicas that we could bring into classrooms and hand to students, because replicas are usually the right weight, they’re the right size, and they have all the decoration of the originals.”

Shortly after the virtual talk Sancinito gave last March, David Menchell, a New York physician and serious collector who teaches workshops on coins and medals, sent her a reproduction set of ancient Roman coins. He followed up with an offer to buy the university genuine coins for study – and asked Sancinito what she wanted.

Once she got over her shock, Sancinito, who does research on the Roman Empire in the third century, asked for some coins from that period. She also told Menchell it would be “awesome” if the collection included some coins from a group found together at a single archaeological site, known as a “hoard.”

Image by K. Webster

Image by K. Webster

Roman silver denarii from the Little Busby Hoard.

In August, the first 38 coins – 37 Roman and one Greek – arrived to form the core of the Dr. David Menchell Coin Collection, now in the special collections section of O’Leary Library. It includes bronze and silver coins from the third century B.C.E. (Before Common Era) to the third century C.E. (Common Era) and includes most of the well-known Roman emperors.

It also includes six Roman denarii from the Little Busby Hoard, a group of 392 silver coins that were buried in the early 200s in Yorkshire, England. The coins in the Menchell Collection were issued under different Roman emperors between 140 C.E. and 180 C.E.

“When coins are found together, I can talk to students about archaeology and the processes of economics and savings patterns,” Sancinito says. “It’s a lot easier to do if you have the evidence of that all in one place.”

Menchell says he plans to donate another group of coins within the month, including some provincial Roman coins and Greek coins, and he will keep an eye out for more ancient Greek coins from different city-states as they become available.

“I’m glad to help in any way that excites her students and propels them forward scholastically,” says Menchell, who had no previous connection to the university. “I think you’re going to remember Nero a lot better when you’ve seen him up close and personal.”

Image by K. Webster

Image by K. Webster

History Assistant Professor Jane Sancinito discusses the Dr. David Menchell Coin Collection in her Ancient Greek History class.

Sancinito, who teaches courses including Ancient Greek History, Roman History and Civilization, World History to 1500 and Pirates of the Mediterranean, is already using the coins in her classes. Through the Emerging Scholars Program, she also engages with one student each year in more intensive research into ancient coins.

Brandon Bulman, a sophomore history major studying Greek history with Sancinito this fall, says it’s “pretty cool” to get to handle and inspect coins from the collection.

“It’s weird to think that people hundreds and hundreds of years ago used them, and now they’re here,” he says.

The Menchell Coin Collection will also be available for teaching and research by other faculty and students in history, economics, business and beyond, says Sancinito, who has created a teaching guide to use with the coins.

“I would love to just get people handling them, because coins are incredibly resilient, unlike so many of the things we have from the ancient world,” she says. “Nothing worse is going to happen to them than spending 2,000 years in the dirt.”

The smallest coin in the collection is a bronze Hellenistic (Greek) obol from ancient Bactria, a Central Asian territory conquered by Alexander the Great, that dates from about 170 B.C.E.

Menchell says the Bactrian obol is just one example of how important coins are to the study of ancient history, because little other archaeological evidence of the Bactrian civilization remains.

“We have a whole lineage of Bactrian kings based just on their coins,” he says.

Image by K. Webster

Image by K. Webster

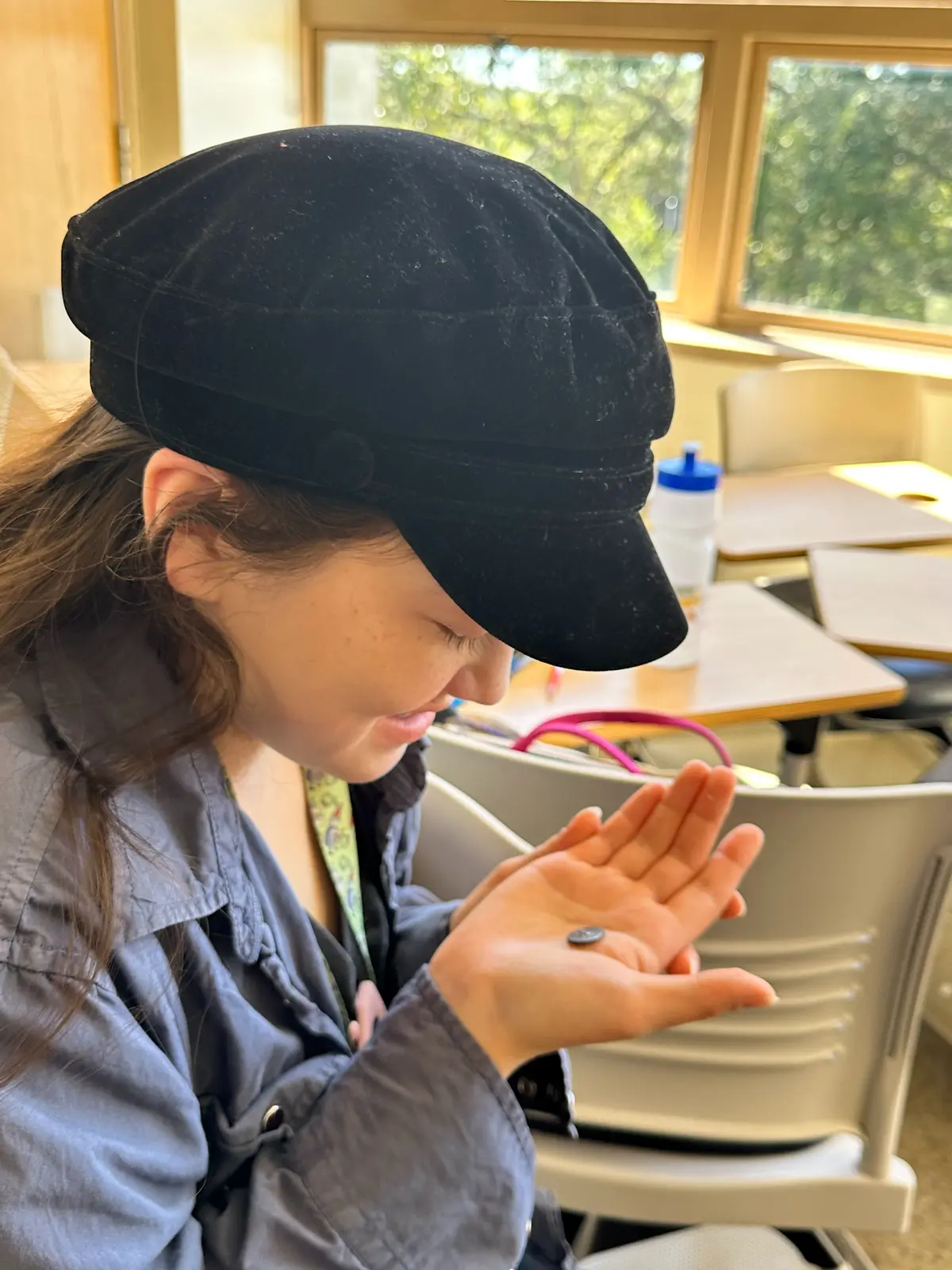

Graphic design major Eve Kim examines a Greek obol.

The largest coins in the collection are two bronze Roman sestertii from the first decades of the Common Era. One depicts Caesar Augustus but was produced by his stepson, Tiberius, and has a temple on the reverse side; the other depicts Emperor Claudius and a robed female figure, “Liberty,” on the reverse.

“In Roman coinage, usually there’s an emperor or empress on the front and a female deity representing a virtue on the back,” Sancinito says.

Even coins depicting the same emperor are full of historically significant symbolism, she says.

“When does the emperor appear in military dress? When does he appear with a crown? When is it a plain bust? All of these variations tell you something,” she says.

The History Department is planning a public event to introduce the coin collection and Menchell to the university later this year.